The Role Of Women In Victorian England

‘The man’s power is active, progressive, defensive. He is eminently the doer, the creator, the discoverer, the defender. His intellect is for speculation, and invention; his energy for adventure war, and for conquest.. but the woman’s power is for rule, not for battle – and her intellect is not for invention or creation, but for sweet ordering, arrangement, and decision… she must be enduringly, incorruptibly good; instinctively, infallibly wise, wise not for self development, but for self-renunciation: wise, not that she may set herself above her husband, but that she man never fail from his side.’

(John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies, 1865, part II)

In this quote, John Ruskin, an art critic and prominent social thinker, highlights how men and women were situated within society during the 19th century. The Victorian era can be attributed to the forming of strict gender ideals and stereotypes. Men and women were allocated specific roles which led men to hold more power over women, and therefore significantly disadvantaged during this era.

Historians call this ‘separate spheres,’ and it means that a man’s place was in the world of economics and business while a woman was a trophy of the home. Separate spheres worked alongside Darwin’s theory, the ‘Survival of the Fittest’ which placed men higher on the evolutionary ladder.

Women and Work

These constructions on gender meant that all aspects of society became gendered, including the world of work. In 1830, wives often assisted husbands in small businesses, but by the 1890s work and home were commonly separated. Men left domestic service, largely down to the shift from agricultural to heavy industrial work. It is calculated that whilst most men worked, only one third of all women were in employment at any time in the 19th century. Compare this with 1978 when two-thirds of women were in employment.

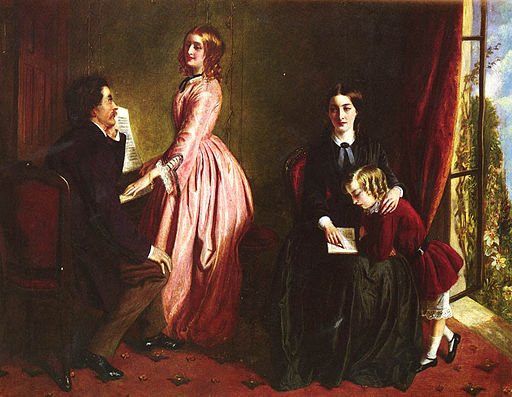

So, whilst women had no rights to sue, vote or own property, they were able to work. But for the upper-middle class, many women never worked outside the home. Women were expected to live up to the image of ‘the angel in the house.’ In other words, be the perfect wife and mother.

Women’s Movement

Despite the strict stereotypes set in Victorian society, the first signs of a feminist political movement began in this era. By the 1850s, this first feminist movement focused on equality in education, work and having electoral rights, like the right to vote.

However, Queen Victoria did not support the feminist movement – despite being a powerful monarch in her own right. She called feminism a ‘wicked folly,’ suggesting that ‘God created men and women differently- then let them remain each in their own position.’

This movement did not make significant legal gains for women, but things had heated up by the first decades of the 20th century. But we must not forget that stereotypes established in the Victorian era lasted longer than the era itself – and many are still visible within some aspects of modern society.