Charles Babbage And The First Computer

If you’ve ever wondered about the invention of computers, you might think of Alan Turing, and those massive banks of computers that sent the Apollo to the moon. But even by then the idea of a computer wasn’t exactly new. In the early 19th century, there was Charles Babbage—a man whose brilliant mind conceived the fundamental principles of modern computing, a good century before they became reality. There was just one slight problem: he was just a bit ahead of his time.

Babbage The Problem Solver

Born in 1791 in London, Charles Babbage was a clever bloke. He was a mathematician, inventor, and philosopher. From a young age, he was a bit of a prodigy, showing an insatiable curiosity and a knack for solving problems. By the time he attended Cambridge University, Babbage was already questioning the limitations of existing mathematical methods.

In the early 19th century, mathematical calculations were laboriously done by hand, often riddled with errors. It was all long division and chunking – no phones or calculator papers in your GCSEs back then. Babbage, frustrated by these inaccuracies, asked himself a revolutionary question: Could a machine do this work more reliably? From this question arose his first major invention: the Difference Engine.

Making A Difference… Engine

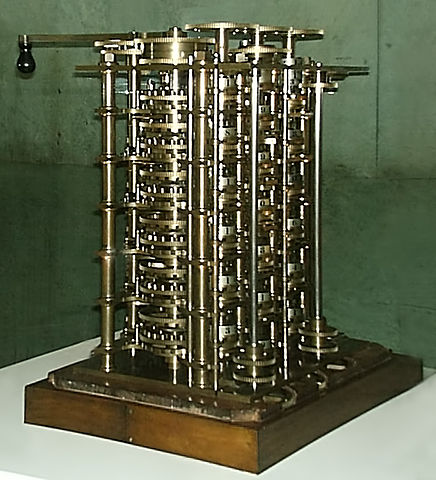

The Difference Engine (pictured) was designed to automate the production of mathematical tables, eliminating the errors inherent in manual calculation. Essentially, it was a calculator powered by steam, using gears and levers to perform those tricky calculations and keep track of all those ones to carry. Babbage envisioned it as a tool for astronomers, navigators, and engineers—anyone who relied on precise calculations.

Work on the Difference Engine began in 1822, with funding from the British government. However, the machine’s complexity soon became a stumbling block. With over 25,000 precision-engineered parts needed, the technology of the time simply couldn’t meet Babbage’s exacting standards. Sadly for Babbage, his project was eventually abandoned, unfinished, in 1833.

From Calculators To Computers

While the Difference Engine was impressive, it was the Analytical Engine that cemented Babbage’s place as the father of computing. Conceived in 1834, this machine wasn’t just a calculator—it was a general-purpose computer. The Analytical Engine had all the core components of a modern computer:

• A Mill: The equivalent of today’s CPU, it performed mathematical operations.

• A Store: A memory unit for holding numbers and intermediate results.

• Input and Output Devices: Punch cards would input data, and a printer would output results.

• Sequential Control: It could execute instructions in a specific order, akin to modern programming.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the Analytical Engine was its programmability. Babbage envisioned using punch cards, similar to those used in looms for weaving patterns into fabric, to instruct the machine. This meant it could solve a variety of problems, not just a single task—a revolutionary concept in the 1830s.

Charles Babbage Was His Own Worst Enemy

Despite his genius, Babbage’s perfectionism and constant tinkering meant that he never completed a single working model of either the Difference or Analytical Engine. Additionally, his difficult personality alienated potential supporters, and the British government eventually withdrew funding.

Another major obstacle was the technology of the time. Precision engineering in the 19th century wasn’t advanced enough to produce the intricate parts Babbage’s machines required. As a result, his designs remained theoretical blueprints, gathering dust in archives for decades.

Though he never saw his machines come to life, Babbage’s work profoundly influenced future generations. In the 20th century, his ideas were rediscovered and celebrated as the foundation of modern computing. Alan Turing, often considered the father of computer science, was heavily influenced by Babbage’s concept of a programmable machine.

In 1991, a team at the Science Museum in London built a working Difference Engine using Babbage’s original designs. The machine worked flawlessly, proving that his ideas were sound and that it was the limitations of his era that had held him back. So next time you boot up your computer or pull out the calculator on your phone, spare a thought for Charles Babbage. Without his temporally misplaced intellect, who knows how differently things could have turned out?