William Hogarth and the Birth of Political Satire

These days we think of satire as something not only of popular entertainment but of necessity. Any democratic government must be open to it, whether they like it or not – usually the latter, though less so when applied equally to their opponents. It is something integral to our politics. But where did it start? Well, some of the first came from the pen and paintbrush of William Hogarth. It helped that he lived in a time of great political corruption, farce and great unpopularity…

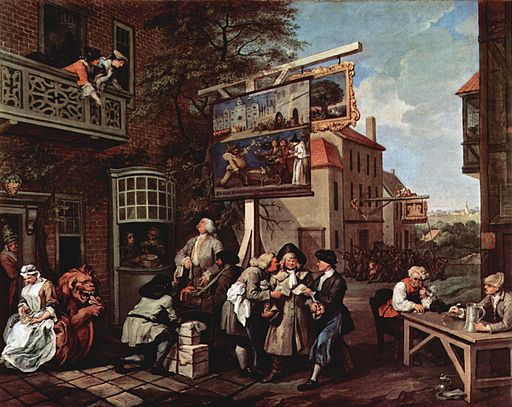

Hogarth first found a ready audience for his cartoon paintings of social and domestic squalor in A Harlot’s Progress (1731) and The Rake’s Progress. By 1753, he had turned his hand to the depiction of English politics, with his work Humours of an Election. This was a painting of the Oxfordshire County Election of February 1745, an event that agitated the minds of both the scurrilous broadsheets and the dons of Oxford’s most distinguished colleges.

The hot issues of Hogarth’s time were unpopular taxation, to pay for a standing army, foreign interference in domestic politics (the Jackobites and Hanoverians) and the influx of migrants. All were topics of heated debate in the coffee houses of both London and Oxford. There was also the pressing issue of the Jewish Naturalisation Act, passed by a Whig parliament in 1753 after royal ascent. Tories condemned the bill as “an abomination of Christianity”, whilst the Whigs sought to boost the interests of banking and the export trade in London and Bristol. Ironically, despite all the ribaldry and indignation of the mob, it was in fact the case that not a single Jew resided in Oxford at the time.

The Oxfordshire County Council Election previously mentioned was one contested for the first time in 44 years, and somewhat curiously, there were two candidates for both Tory and Whig parties. The Tory faction fielded Sir James Dashwood and Viscount Newham whilst the Whigs put up Viscount Parker and Sir Edward Turner. Matters were further complicated by animosity between the Duke of Marlborough, supporting the Whigs, and the Earl of Abingdon and Lichfield, who was supporting their opponents. Both sides were competing for the support of around 4,000 forty shilling free-holders, merchants and shopkeepers. Both sides were prepared to spend lavishly on feasts of roast beef, mutton pies and flagons of strong ale to capture these swing voters. Ideal for any skilled satirist, let alone one such as Hogarth.

Election meetings were held on Friday nights in The King’s Alms and the One Tun Tavern opposite Hungerford market (See his Canvassing for Votes, above). These were not the orderly events of modern times, though. Rather, they usually and farcically descended into riots, drunken brawls and debauchery. College dons from Christchurch, Bailliol and Exeter college contributed lampoons of the proceedings to rival the hacks of Grubb Street.

On the Council election day the recording officer, after several re-counts, brought ridicule on ridicule. He declared both sets of candidates to have won, and therefore the House of Commons had to make a decision on which faction, Whig or Tory, should represent Oxford. As there was a Whig majority in the Commons, this won the day, and victory was conceded to them.

With such material to work with, Hogarth was able to gain much fame, both in his time and ever since, all the way until today, with its plethora of popular satire across all media. In the words of Henry Fielding, he was “one of the most useful satirists that age has ever produced.”