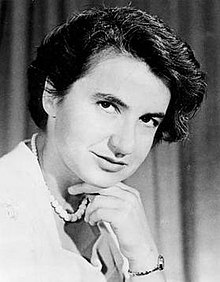

The Woman Behind Our First Understanding of DNA

The ground-breaking work of British scientist Rosalind Elsie Franklin, born in July 1920 was vital to our understanding of molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), and RNA, (ribonucleic acid). The same can be said for that of viruses, graphite and coal. Yet despite the physical chemist’s breakthrough with ‘Photo 51’, the very photograph that revolutionised the science of genetics, Franklin’s work was greatly under-appreciated during her lifetime.

Aged 18, London-born Rosalind enrolled in Newnham Women’s College at Cambridge University, where she studied Physics and Chemistry. In 1946, she moved to Paris where she honed her skills in X-ray crystallography, turning her passion into a career. Rosalind returned to the UK after four years, where London became home once again.

In 1951 Franklin joined the Biophysical Laboratory at Kings College London as a research fellow, where she applied X-ray diffraction methods to the study of DNA. It was here that she made a breakthrough discovery about the density of DNA and found that the molecule existed in a helical conformation.

During her time at King’s one of her fellow scientists was Maurice Wilkins. There was apparently discord between Wilkins and Franklin. This despite the fact they were working together to find the structure of DNA. This culminated in them working separately. Wilkins went to “the Cavendish” laboratory in Cambridge where Francis Crick, his friend, was working with James Watson on building a model of the DNA molecule.

Photo 51, Watson, Crick and No Credit

Watson and Crick saw some of Rosalind’s unpublished data, including “Photo 51,” which was shown to Watson by Wilkins. The photo is an X-ray diffraction image and made Franklin the woman behind the first-ever photograph of DNA.

The picture of a DNA molecule was Watson’s inspiration (the pattern was clearly a helix) for he and Crick to create their famous model of DNA, which they published on March 7, 1953. For this, they went on to receive a Nobel Prize in 1962. Franklin’s contribution went unacknowledged. Only after her death did Crick say that her contribution had been critical.

An Influential Career Beyond DNA

In 1953 Franklin relocated to Birkbeck College, where she studied the structure of RNA and the tobacco mosaic virus. She went on to publish 17 papers on viruses, her group laying the foundations for structural virology.

Since then, Franklin’s work has continued to inspire advances in biology, medicine, paleontology, and many other parts of life. We should certainly be grateful for her lifetime of dedication to pioneering research work, and to the discoveries she made.