The Untimely Death of Rupert Brooke

Last month, a memorial service was held on the Greek island of Skyros to commemorate the death of Rupert Brooke, one hundred years ago.

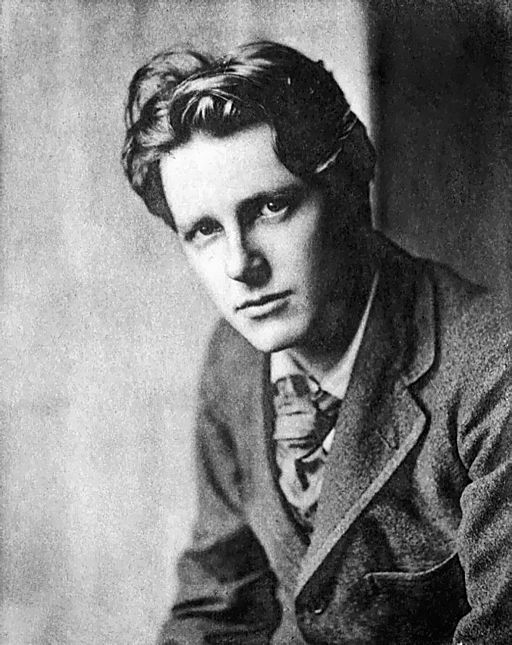

Brooke was the ‘Golden Boy’ of the Georgian poets: WB Yeats famously referred to him as ‘the handsomest young man in England’ and the photograph of him writing outside in his pyjamas is one of the most enduring images of the pre-war era. After signing up himself, his patriotic verse inspired the first wave of recruits to join the war but, although considered ‘godlike’, he was proven to be mortal in April 1915, after being bitten by a mosquito on his way to Gallipoli.

His premature death should have secured Brooke’s reputation forever and it is true that his most well-known work, The Soldier, swiftly became – and remains – one of the nation’s best loved poems. However, ironically, the fame of this poem has been detrimental to his legacy.

A new generation of cynical readers, inured to war because of Iraq and Afghanistan, has begun to scoff at Brooke’s idealism. They say that he would have changed his mind had he lived and that his patriotism would have waned. They cite fellow war poet Wilfred Owen in their arguments, because Owen also published pro-war verse in 1914 before his experience of the reality of battle changed his outlook. Owen (who only, let us be clear, out-lived Brooke by three years) certainly had the blinkers removed from his eyes. He wrote of floundering in mud and blindness and shell-shock. Brooke didn’t – he didn’t have the opportunity to – but should we dismiss his talent because of that?

The problem with Rupert Brooke is not that he died too soon, for that fate has secured the reputation of many, from James Dean to Elvis Presley, but that he died just before his eyes were opened, meaning his version of the war, forged in the initial optimistic stage, has become outmoded, superseded by a more jaded version.

Brooke, like Byron, died in Greece on his way to the action, before experiencing the horrors of war, so he is forever placed amongst those who condone war in general, even though his vision of a ‘foreign field’ has given comfort to generations of relatives over the past 100 years.

Poems such as The Old Vicarage, Grantchester and The Hill show us that a major talent was cut off in its prime. Had Brooke lived, he might have become a different poet. We should not condemn him because he sacrificed that opportunity.