The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

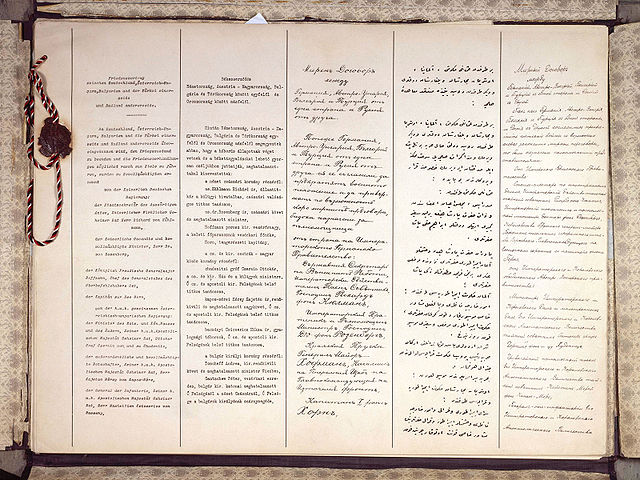

The First World War ended with the signing of two flawed peace treaties: The Treaty of Versailles, the terms of which led directly to the Second World War, and the lesser known but similarly influential Treaty of Brest Litovsk (shown above), signed on 3rd March 1918 between Bolshevik Russia and the Central Powers, which ended Russia’s participation in the First World War. Whilst it could be said that this latter’s effects were largely on a single country, those effects embedded themselves in that countries’ psyche so deeply that they are, to some extent, still influencing decisions there today. As such, and considering the world’s current political climate, it is worth hearing about.

The background to Brest-Litovsk was the catastrophic collapse of Russian society during the years 1914-1917. By 1918, there was an overwhelming desire for land redistribution, an end to chronic food shortages and also to the fighting on the Eastern Front. Equally, in order to gain power, Lenin was prepared to sign such a peace deal no matter the cost. Trotsky was instructed to play for time. Both Lenin and he expected a workers revolt in Germany that would sweep away their old order and in turn inspire similar actions in other countries. They were confident they would be negotiating with like-minded revolutionaries in the near future. And at the time they had good reason to do so. The German population was starving and its country was losing in the war, while on a broader scale, socialism was on the rise throughout Europe. Yet, despite it all, in the event history took a different course.

The proletariat were not keen on revolutionary solidarity as opposed to expressions of theoretical solidarity with their brothers in far-off lands. The Bolsheviks signed the treaty under overwhelming duress, determined at the first opportunity to renege on the deal. The ancient Baltic states were succeeded to Germany and land in southern Russia went to the Ottoman empire. Russia was forced to abandon claims on Poland, Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and the Ukraine. In all, 150,000 square km of Russian territory was lost. Lenin’s insistence that the delegation agree to Germany’s draconian demands caused bitter and lasting divisions within the Communist Party, with the consequences proving dire for many. When Lenin died and Stalin came to power, his replacement wasted no time in taking revenge. Throughout the 1930s a series of brutal purges liquidated Trotsky’s entire family, as well as all those who had worked with him throughout his long career.

Nevertheless, Communist Russia did gain some immediate and important benefits from the treaty, from its point of view. The signing of the document enabled the communists to concentrate all their resources on fighting a successful civil war, for one. Between 1920 and 1934 the Russian aristocracy, the Kulaks, and swaths of the middle class, all became “none persons”, replaced by the “New Soviet Man”. Communist political theory was replaced by communism as religious belief. The old Bolsheviks were denigrated and sent to the gulag. Stalin became the new God of the Soviet Union. Much of the territory, and certainly sphere of influence, lost by the treaty of Brest-Litovsk was regained under Stalin after the Second World War, most notably Poland.

Not every land was taken back, however, however; Finland, a satellite state to Russia, and the Crimea remained independent, and thus there remained a stain of embarrassment and anger on the red flag. Nationalists in modern Russia have not forgotten the humiliations imposed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and the subsequent events of 1918 still find echoes in much of Russian foreign policy as a result, making it markedly relevant to European political History.