The Picture Postcard: A First Fast-Communication Industry

An Innovative Method of Modern Communication

Since lockdown began and restrictions were placed on physical interaction, it has been interesting to see the impact upon our virtual connectivity – screen-time has skyrocketed in an attempt to satisfy our inherent desire for human connection. Advancements in technology have been allowing us to feel better interconnected for over a century. And whilst it may sound strange, the creation of the humble picture postcard is a prime example.

The Picture Postcard Boom

From 1898-1918 the predominant method of communication was the picture postcard. Its conquest of British society was truly remarkable; it is estimated that around 6 billion postcards were in circulation in Britain during the reign of Edward VII (1901-1910), which averages at roughly 200 postcards sent per person. These figures do not include postcards purchased for private collections, meaning the total number is likely to be much higher in reality.

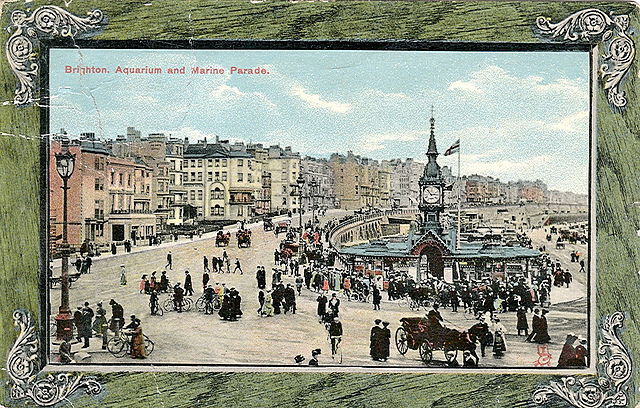

The postcard’s popularity correlated with the height of the British Empire. It meant there was a broad scope of imperial imagery available, in addition to domestic depictions. Indeed, postcard pictures covered almost every aspect of society imaginable. Landscapes, monarchy, transport, humour, animals, cartoons, portraits, families, buildings, sports, wars, cultures – the list of genres is endless.

A Culture of Speed

As a symbol of contemporary progress, the postcard was a modern invention that combined advances in printing, photography, industrialisation, transportation and postal regulations, culminating in a culture of speed.

Difficult processes and bulky equipment required for photography were made obsolete with the invention of George Eastman’s instamatic camera in 1888, making it easier for firms to capture and print images. Advances in transport also meant that the post was delivered up to six times a day, making communication faster than ever been before.

However, it was the modernisation of postcard design that ultimately led to the ensuing postcard mania. Plain postcards with no picture were introduced by the General Post Office in 1870 and permitted for private production in 1894. Initially, very few British firms began publishing, owing to the hampering regulation that restricted the size of postcards to 4.5 x 3.5 inches; a size that was unappealing to collectors as cards failed to fit into collection albums. Yet, by 1898, the desired sizing was standardized and the boom began – 75 million were sold in the first year.

However, it wasn’t until 1902 that the Post Office permitted a dividing line across the back of the card, to separate a message from the address. This meant that the image was allowed to take up a full side on the reverse and thus the postcard we know today was born. With limited space necessitating a brief, swift message, the postcard’s new design contributed to the feeling that the postcard was a sign of the times.

A Penny For Your Thoughts

The following two decades saw Europe buried beneath picture postcards. At the cost of just one penny, the price of the postcard contributed to its success as a truly democratic item. The breadth of its reach across all classes, genders, and ages was unparalleled in contemporary collectables.

Messages were very brief and conversational, such as ‘Hope to see you this evening’ or ‘sent with affection to swell your collection!’. During its initial phases as a new media, critics bemoaned the ‘postcard pest’ for its destruction of literary style, the impropriety of strangers being able to read personal communications, and the potential for indecent imagery.

Criticism eventually subsided as the upper classes embraced the medium, with the size of a collection coming to represent an individual’s wealth. Even William Gladstone and Queen Victoria were said to be patrons of the postcard. Aside from the postage stamp, there had never been a more pervasive fad for a material item.

Demise

The picture postcard saw its demise as a result of the increase in Inland postage following World War One. Sales plummeted, but the postcard remains a novel way to stay in touch with friends and family from abroad.

As a small image, often adorned with captions and funny anecdotes, it can be argued that the postcard was the forerunner of today’s texting, or even meme culture. However, the love and care put into purchasing, writing, and sending a postcard is unrivalled in modern communication. So, if you’re looking for a nice activity to fill an afternoon during lockdown, why not pick up a pen and write to a friend to honour over 100 years since Britain became utterly consumed by the humble picture postcard.