“The Little Woman who made a Great War”

These were the words with which Abraham Lincoln greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe and her sister when they visited the President at the White House on his invitation in 1862. Harriet’s family had long been passionate believers in negro emancipation, and active in aiding the Underground Railway’s mission in helping renegade slaves pass into the Northern Territories. The issue of slavery was threatening to tear the young nation apart at the time, with southern planters believing in white supremacy and therefore slaves their property, no more than chattels. This belief was was enshrined in law so that an escaped slave had to be returned to their southern owners and to hide or assist such a fugitive was a criminal act.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, on June 14th, 1811. She was the wife of a Congregation Minister and of course the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The family was deeply religious and she was steeped in a culture of sin, atonement and salvation since childhood. She lived at a time when young women were expected to marry, bear children and concentrate on duties at home. But American society was changing, particularly in the north and the new territories of the western interior. Opportunities existed for educated middle class women to earn their own money by writing articles for newspapers and the newly created women’s journals.

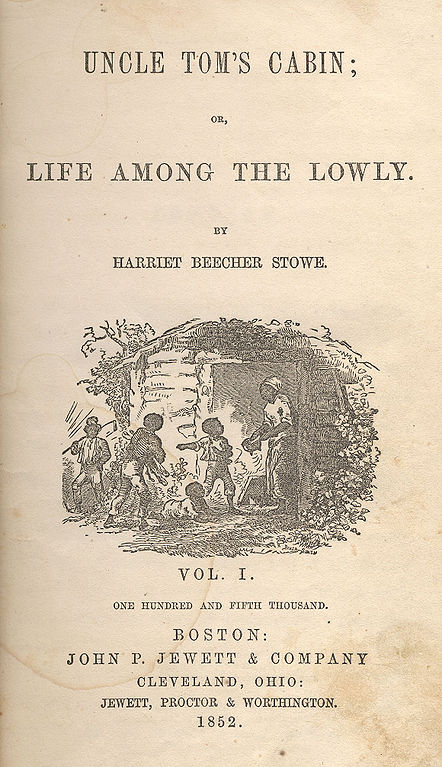

Harriet wrote her story by candle-light in her farm kitchen after putting her six children to bed, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin first came out as a serial in an anti-slavery newspaper. It was published in book form in the spring of 1852 (the cover is shown above). Within a year it had sold 300,000 copies in America alone. It was equally popular in Britain and was quickly translated into several foreign languages, its sales running into many thousands.

The success of her book remained international. In England, Lord Palmerston read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and claimed it was one of the factors which, a decade later, persuaded him not to intervene in the Civil War on behalf of the Confederacy, a catastrophic blow. The book caused outrage in the south. Efforts were made to ban it, but in Charleston book sellers could not keep up with demand.

Within two years at least 15 Uncle Tom publications were produced in the south, with such titles as Uncle Robin in his cabin in Virginia and Tom without one in Boston. These were crude justifications for the south’s institution of slavery. None mentioned the savage whipping of men and women, the sale of family members to repay debt, or the murderous working conditions under broiling sun, on the cotton, tobacco and sugar cane plantations of the Deep South.

However, as time went on, Uncle Tom became an epitaph for any black person who behaved with fawning servility towards a white person. Frequent music hall productions transmuted the original story into grotesque melodrama. In the original version, Tom is portrayed as a Christ-like figure, intended as an inspiration to the Christian abolitionists who marched to war and died “to make men free” as one of the North’s favourite hymns has it.

Harriet died on July 1st, 1896, aged 85, after living a very full Christian life dedicated to education and Christian causes.