A History of Tennis

Wimbledon, the most prestigious of events in the tennis calendar, is almost upon us. This annual championship has been held in June ever since 1877. The origins of the game of tennis itself is much older.

Although some historians claim that tennis dates back to the ancient Egyptian civilisation, there is little evidence that links the sport to the ancient world. It isn’t until the eleventh and twelfth centuries that clear evidence of the game emerges.

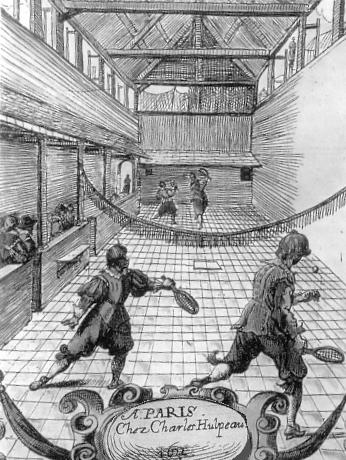

It was within the confines of the French cloister that the first signs of the game emerged. A crude handball called jeu de paume (depicted above), which means game of the hand, was played by French monks against a wall or over a rope strung across a courtyard. The game grew in popularity amongst the religious orders, and soon spread to the richer nobles. At this stage, bare hands were still used to hit the ball rather than a racquet or bat, so leather gloves were developed to protect the player’s palms. In time, these gloves had webbing woven between the fingers to provider a wider base for the wool, cloth or cork ball to hit against. These gloves were later replaced with solid paddles with a short handle.

When it came to the tennis court itself, the Tennis and Racquet Association said that, “The shape of the court, as we know it today, evolved slowly over the Middle Ages, but by the end of the 15th Century, approximate dimensions had been agreed, an overall length of 90 ft and a breadth of the 30 ft.”

By the thirteenth century, France’s manor houses and monasteries held over 1,800 courts in France. Such was tennis’s popularity diversion that the pope and King Louis IV tried to ban it, as it was diverting people from religion. However, their ban was unsuccessful. In England, both King Henry VII and Henry VIII are known to have loved tennis. Their keenness for the game led to the sport becoming known as the Game of Kings. In order to keep the general population from playing tennis, repressive measures were taken in both England and France to restrict the game to the noble class only.

The traditionally shaped wooden frame racquet strung with sheep gut was in common use by 1500, as was a cork-cored ball. It was in 1625, when a new court was built at Hampton Court in London, that “real tennis,” was born; and a net was placed across a narrow indoor court. The popularity of tennis within royal circles was illustrated again and again. English royalty often played in courts at Windsor, Whitehall, Westminster, Wycombe and Woodstock, and in Shakespeare’s Henry V, the hero, having been insulted by the Dauphin with a gift of tennis-balls, threatens to, “Strike his father’s crown into the hazard” and warns him that, “He hath made a match with such a wrangler that all the courts of France will be disturbed with chases.”

Both King Charles I and Charles II loved the game, and surviving documents from their respective reigns claim that they used to get up at five or six in the morning to play. After a visit to the tennis court at Whitehall, Samuel Pepys wrote of Charles II, “…but to see how the king’s play was extolled, without any cause was a loathsome sight, though sometimes he did play very well and deserved to be commended, but such open flattery is beastly”.

Tennis’ popularity fell away during the 1700s, but in 1850, with the invention of vulcanised rubber, bouncier balls took the game outdoors onto grass courts. However, it wasn’t until 1874 that Major Walter C. Wingfield patented the equipment and rules for modern tennis.

The Wimbledon championships were first held in 1877 on a croquet lawn belonging to the All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club. At first only men were allowed to play, but then, in 1884, women were allowed to join in as well. From its early beginnings in a French monastery through the years when it was reserved for kings, to today, the game is as popular as ever and played all over the world.