The Leakey Family and Revelations under the Sun

Frequently referred to as the ‘Father of archaeology and anthropology’, Louis Leakey was born on 7th August, 1903, in Kabete, Kenya; the son of British missionaries.

Leakey’s fossil discoveries in East Africa were the first to prove that human beings had developed thousands of years before previously believed. He also showed that the dawn of humanity began in Africa, rather than in Asia, as earlier fossil discoveries had suggested.

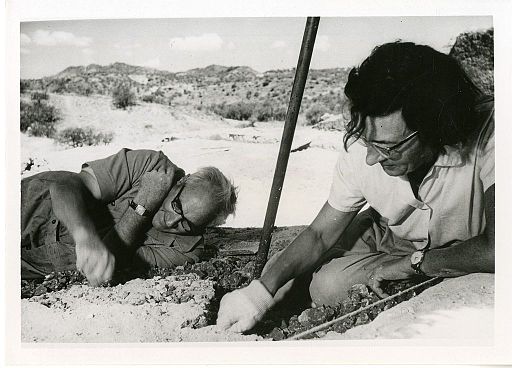

Although born in Kenya, Louis embarked upon archaeology and anthropology as a career after studying at Cambridge University. Concentrating his work in East Africa in 1924, in 1931 he moved his research to the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. This was to become the most important site of his career. With his wife Mary and their sons, Louis began an intense examination of the area in relation to the fossil records of evolution.

The site revealed largely animal fossils and a number of early stone tools, but it wasn’t until 1959 that a hominid (human-like) fossil was found, being unearthed by Mary. This unique find was given the name Zinjanthropus. It was 1.7 million years old. After further years of research, however, the Leakey family realised that Zinjanthropus was not a direct ancestor of modern man. This conclusion was reached after Louis uncovered other hominid fossils at Olduvai Gorge between 1960–63 which came from a group of ancestors he called Homo habilis; a more advance hominid which was on a direct evolutionary line to Homo sapiens (modern man).

Although scientists and archaeologists alike disputed the Leakey’s findings, the significance of their discoveries was soon widely accepted. Indeed, these early, breakthrough studies of human development have since helped archaeologists and anthropologists make further strides towards understanding the evolution of mankind and the world, both sociologically and environmentally.

It is not always our own searching that helps us find where we came from, though. Nature can give us answers too. In recent weeks, one of the effects of the intense heat that has swept Europe has been to sear away some of the camouflage of history, to the extent that archaeologists have found themselves uncovering more fascinating evidence of early life. Speaking to the BBC about the appearance of prehistoric settlement outlines amongst the crops of the UK (not to mention those of Roman villas and forts), Dr Toby Driver, Senior Aerial Investigator with the Royal Archaeological Society, said, “So much new archaeology is showing, it is incredible; the urgent work in the air now will lead to months of research in the office in the winter months to map and record all the sites which have been seen, and reveal their true significance.”

It is the uncovering of some of the earliest human sites in the UK that is causing the most excitement. The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales has been documenting the effect the heatwave is having on the countryside. They are particularly intrigued by a series of Bronze Age barrows and prehistoric settlements across the Llyn Peninsula. Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland, the increased temperatures have led to a drop in the level of the Spelga Reservoir in County Down, revealing a previously undocumented ancient road.

Since the outstanding contributions of Louis and Mary Leakey in the early part of the twentieth century, archaeological study and the understanding of the rise of the human race has gone from strength to strength – but as we have recently learnt, there is still much more for us to uncover and understand about the societies of our past.