Maps And Their Historical Development

Why Are Accurate World Maps So Hard To Create?

The next time you look at a world map, ask yourself, “Is this world map wrong?”. Maps are everywhere, hanging in classrooms or your home study wall and appearing on websites. But have you ever wondered if the world map you know is actually accurate?

World maps are complex representations of the Earth’s surface that involve significant compromises and distortions. The challenge arises because the Earth is a three-dimensional sphere, but maps are flat, two-dimensional representations. When translating the Earth’s curved surface onto a flat map, cartographers must decide what to keep accurate and what to distort. This has led to the creation of various map projections, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

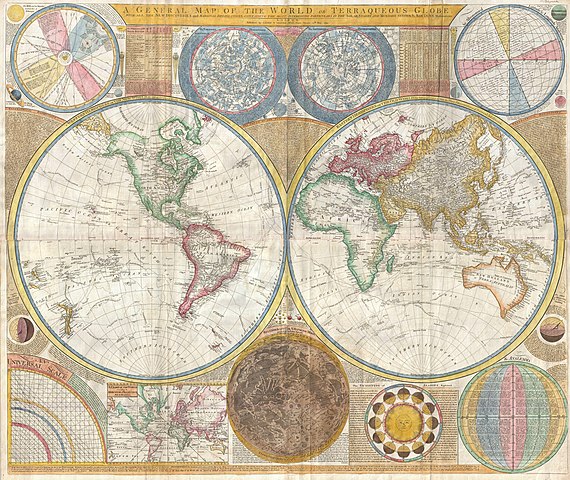

While it’s unlikely you use these maps in an educational environment, the Babylonians (600 BCE), Greeks (6th century BCE), and the Byzantine monk Ptolemy, (2nd century CE), used travelers’ accounts and mathematical calculations to depict the world’s basic layout, often featuring one to three continents. With more data and exploration, they could have created even more accurate maps.

The Mercator Projection

However, the typical classroom map you see is likely based on the more (relatively speaking) recent Mercator projection, developed in the 16th century, informed by both historical and new knowledge from global exploration. The creation of accurate maps remained challenging, however, because full geographic information was still limited; as such, maps were built painstakingly from the notes, accounts, and observations of these explorers. Despite these limitations, the Mercator projection was revolutionary for its time because it preserved angles and directions, making it useful for navigation. However, the first Mercator maps also distorted the true sizes of continents and oceans, especially those farther from the equator.

Some notable distortions in the Mercator projection included:

Greenland, Siberia, Canada, and Antarctica appear disproportionately massive.

Greenland alone looked roughly the size of Africa, even though Africa is actually 14 times larger.

Africa appears smaller than North America, although it is, again, larger.

The Gall-Peters Projection

In contrast, the Gall-Peters projection, developed in the 19th century, was designed to preserve the relative area of land masses, offering a more accurate sense of the size of different countries. Although this projection distorts the shapes of continents, making them appear stretched or squashed, their relative sizes are more accurate, with Africa shown as larger than North America and Europe. This projection sparked political controversy, which may have limited its popularity. Other projections have since been developed to balance distortions in size, shape, and distance, but the Mercator and Gall-Peters projections remain among the best-known.

Maps Can Be A Political Challenge

Thanks to satellite imagery and advanced technology, such as Google Maps, we now have the capability to create accurate global images. While the physical challenge of gathering geographical data has been largely overcome, today’s challenge lies in creating map projections that are politically acceptable in a complex geopolitical landscape. So, if you’re looking for a truly accurate and politically neutral view of the world, the best option may still be a globe!

If you have an interest in studying Geography or History, Oxford Open Learning offer the chance to do so at the levels listed below. You can also Contact Us.