Alzheimer’s And Brain Microbiomes

The Impact Of Microbiome On The Brain

The human microbiome includes trillions of microorganisms such as fungi, yeast, bacteria and viruses, most of which are located in our gastrointestinal tract. When these healthy biomes are disrupted and become imbalanced, a “pathobiome” may form which can cause numerous health problems. Traditionally, scientists believed that the brain was a sterile environment, protected by the blood-brain barrier. However, recent research has suggested that the brain may possess its own unique microbiome that could impact the health of the brain and is redefining our understandings in neuroscience.

Microorganisms In The Brain

In advanced imaging and molecular studies of brain samples from those with Alzheimer’s and those without, researchers found evidence of microflora in all samples. However, there was up to seven times more bacteria and different profile proportions in the Alzheimer’s samples. Many of these microbes are thought to have functional roles, perhaps as immune system regulators or in sustaining our metabolic health. But how can microorganisms enter across the blood-brain barrier, a filter designed to keep out pathogens and toxins? One theory is that the blood-brain barrier becomes compromised and damaged due to ageing or inflammation.

Immune Response And Neuroinflammation

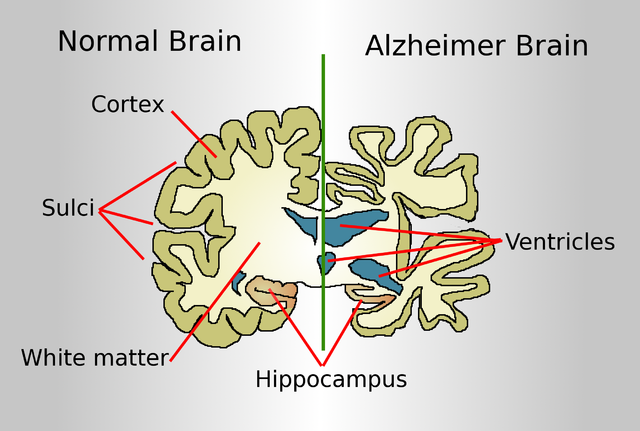

Once microbes have entered the brain, it is thought that in an imbalance in microfauna can lead to the inflammation. If this inflammation becomes too extreme, it can lead to the damage of brain cells that lead to neurodegeneration. A known characteristic of Alzheimer’s is the buildup of toxic proteins that include beta amyloid and tangles of tau. These proteins activate the brain’s immune cells which are known to cause inflammation as a response mechanism. If microorganisms are causing inflammation through this triggering of immune responses, it can signal a link between their presence and an increases in the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. It is also believed that microbes in the gut can have an impact on the health of the brain – known as the gut-brain axis. New research is investigating how gut bacteria influence the brain through the nervous and immune systems.

Advances In Alzheimer’s Treatment

If it is proven that microbes really do influence neurodegenerative diseases, new treatments could help to stem their impact, such as probiotics or specialised diets. Although in its early stages, a promising study showed that treating mice with antibiotics weakens the signs of Alzheimer’s by decreasing the amount of amyloid-ß (Aß) peptides in the brain. This suggesting that microbes were indeed playing a part in their neurodegenerative decline.

If you have an interest in studying Biology or Human Biology, Oxford Open Learning offer the chance to do so at several levels. You can also Contact Us.