“A War Imagined”: Invasion Literature

In the 10 years prior to the outbreak of war in 1914, Britain experienced a period of moral panic. It was a common view amongst the older generation that the youth of the country lacked “moral fibre”. This unease was rooted in the social climate and cultural assumptions of late Victorian Britain. The products of our public schools were considered to lack a certain masculinity. The older generation believed that the cure for this was, not to put too fine a point on it, to be had in bloodletting; a short, sharp war that would instil Christian virtues, patriotism and “backbone”.

London was also home to thousands of German shopkeepers and waiters. Many were Jewish immigrants who had settled in Soho and the East End. Hostility and resentment against foreign immigrants who had done so was common at the time, with foreigners being generally despised, heightened by an arms race in response to the Kaiser’s expansion of the German Navy and his country’s economic competition with Britain.

It was against this background that in 1903, Erskine Childers published The Riddle of the Sands: A Record of the Secret Service. The book was immediately popular – an invasion novel that was to influence the whole spy and espionage genre, perfected by John Buchan, Ian Fleming and John Le Carre in years to come.

In his novel, Childers imagines an amphibious invasion across the North Sea by German troops transported in barges hidden in the sandbanks off the Frisian coast. In what was to become a hallmark of the genre, fact was skilfully mixed with a large dose of fiction. At the time, few imagined a German invasion across land as it was assumed they would not violate Belgian neutrality.

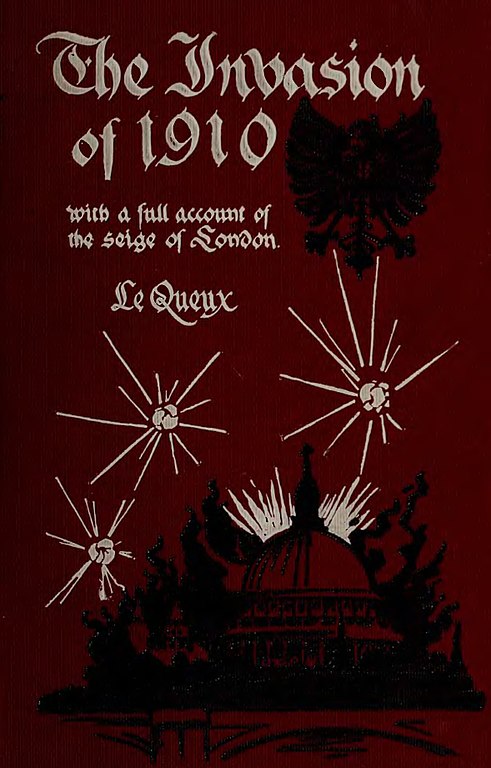

Three years after the publication of Riddle of the Sands, an Anglo-French journalist, writer and minor diplomat, William le Quex, published an even more popular invasion fantasy, The Invasion of 1910 (above), which was enthusiastically endorsed by no less a figure than Field Marshall Earl Roberts, who regularly lectured schoolboys on the need to prepare themselves physically and spiritually for war. The novel was serialised in Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail, a wide-circulating broadsheet newspaper popular with its growing mass-readership. Le Quex himself was a clever popularist and publicist, eager to boost sales and not too particular about how he did it. He organised a publicity campaign which featured young men dressed in German uniforms marching down London’s Regent Street, for example. This stunt alone successfully fuelled the anti-foreign resentment and xenophobia already present in the population, helping it to become a marked feature of popular sentiment by 1914.

Such novels helped inspire thousands of young men, who had been schooled to believe in the twin myths that war was an adventure and self-sacrifice a duty, to volunteer for service in the Great War – and dying in the Somme.

Between the wars the genre became a popular medium for amateur secret service agents working for the British Crown, in order to supplement their very meagre government salaries. For example, Maxwell Taylor, the first director of MI5, used his detailed knowledge of the British Secret Service to supplement his salary by publishing a number of novels. And whilst his were of a distinctly low quality others such as Rudyard Kipling and John Buchan subsequently raised the quality of the genre to the level of well respected literature.

Spying, espionage and treachery have become a staple diet of popular imagination, sustained by the political events of the 20th and 21st centuries; the threat of communism in the 1920s, fascism in the 1930s and the Cold War. Stories of the genre remain to this day a staple fare of holiday reading, film and TV drama.