1858: The Heatwave that sanitised London

2018 has seen the world catch fire. Forests have blazed in searing temperatures in places as far apart as southern California and Canada, Sweden and the arctic. Temperatures of 40 degrees have been recorded in Portugal and Spain, whilst central London has experienced a large number of days when it has climbed over 30. There has been little to cheer for farmers, gardeners, trees and the environment as a whole. Outside of the holiday-maker, it has been a very destructive season. During the Victorian era, though, when another such event fell on London, the conditions actually brought about one of the most significant and beneficial technological and social advances in British history.

In 1858, similar weather patterns hung over the Northern Hemisphere, choking the capital. Worse than today’s monoxide pollution, it was the unbearable stench of the city’s streets which plagued Victorian Londoners. Not only did they have to suffer the results of a grossly inadequate sanitation and drainage system for a city of some 2.5 million people, but there was also a total lack of air conditioning and refrigeration. Waste was thrown and left on the street or poured into the Thames, which was where most people got their drinking water from. The city’s crumbling brick-lined sewers leaked, contaminating household and community wells alike. Industrial waste, mainly from the many tanneries lining the river, was also discharged directly into the river. The city had hundreds of cesspits which leaked methane gas, often catching fire and adding even further to the noxious pollution.

In 1831 cholera had claimed over 6,000 lives. Between 1834 and 1854 that number became 10,700. To make matters worse, the heat of 1858 caused the Thames waterline to drop, exposing yet more pollution, all left to sit on its banks without removal. Carbolic acid was spread over it in the hope that it might make a difference, but this was unsuccessful.

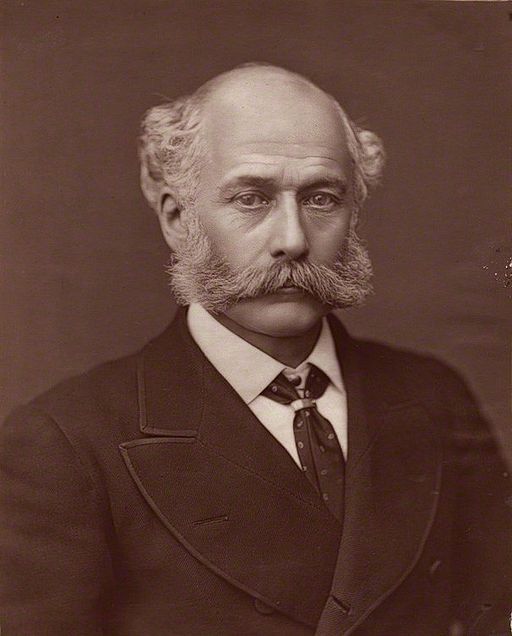

Eventually things became so bad that the press, led by The London Standard and Illustrated London News, put pressure on the government to take significant action. And as the stench infused the committee rooms and libraries of the House of Commons, they finally reacted. Disraeli, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, provided the finance to set up the Metropolitan Board of Works, on 9th August, 1858. A brilliant engineer named Joseph Bazaigette (pictured above) was commissioned to design and build a state-of-the-art sewage system together with pumping stations serving the city.

Bazaigette’s system proved to be the greatest contribution to public health in Victorian England, far more effective than the medicine of the time in combating its epidemic diseases like cholera and typhoid. Indeed, it proved to be the template on which the city sewage and water systems were constructed well into the modern era. The construction of London’s new sanitation and water supply helped convince the Victorians of the need for centralised, properly funded state intervention in the economic and social affairs of a growing urban, industrial society. The self-help and laisse-faire philosophies of Samuel Smiles were no longer adequate for the age. All, indirectly, because of the heat and the hideous effects it had wrought. Doubtless the advances would have been made in time, but not so immediately.

The first steps towards the erosion of our ozone layer were being made back then. One can only imagine the pre-Bazaigette London of 1858 all these years later, in our modern heatwave, when we have removed so much more of it.