A History of Strife: Crimea and the Tartars

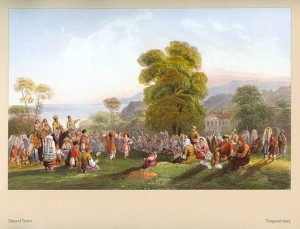

Several recent articles for this site have focussed on the current situation in Ukraine. For a final piece, it may be interesting and relevant to tell the story of one minority, non-Slavic group of people, who occupy the northern part of the Black Sea region of the Crimean peninsula. In areas of unrest such as this, knowledge of such histories can help understand the problems and how they have developed through the generations.

Several recent articles for this site have focussed on the current situation in Ukraine. For a final piece, it may be interesting and relevant to tell the story of one minority, non-Slavic group of people, who occupy the northern part of the Black Sea region of the Crimean peninsula. In areas of unrest such as this, knowledge of such histories can help understand the problems and how they have developed through the generations.

The Crimean Tartars are settlers who make up around 12% of the region’s population, speaking Turkish, Tartar and Russian. In addition there is a sizeable Diaspora living in Romania and Bulgaria as well as in Western Europe (Germany and Italy), the Middle East and North America. These emigrants are Tartars whose descendants have fled from Russian persecution in the last three centuries. Eighty-two percent of the Crimea’s population is Russian, enthusiastic supporters of President Putin who voted in the recent referendum for intergration with Russia. The Russians have always regarded the Crimea as integral to the Russian state, vital to its security and the playground of the rich since the days of the Tsars.

Up to the 18th century, the Crimea was one of the strongest powers in eastern Europe. The Tartars’ loyalties were to Islam and an independent Khanate. Its whole economy and social cohesion was based on the capture of Ukrainian and Russian slaves (“the harvest of the steppes”), for the sale to the Ottoman Empire and Turkish dealers. It has been calculated that around three million people of slave origin were traded in this way and sold into bondage.

However, the Turks and their allies were comprehensively defeated in the Russo-Turkish war of 1768 – 74. Crimea subsequently became an independent country under Russian protection. It was an uneasy relationship, however, and when the Russian Revolution erupted, it broke. During the Russian civil war that followed, the Crimea became a stronghold of the White Russian armies, until the eventual triumph of the Reds. Subsequent Bolshevik revenge was to be horrendous.

During the Stalinist purges the Tartar elite was wiped out, food was confiscated and shipped into central Russia, and ultimately collectivisation was forced on the people. In one year (1928-29), 100,000 starved to death. Between 1931-33 a second enforced famine killed another half-a-million.

After all this persecution and suffering, in World War Two many Tartars fought for Hitler in the Tartar Legion, though equally, many fought as partisans for Russia. In 1944, however, the punishment for those of the Tartar Legion was nevertheless visited on the entire Tartar population. There was mass deportation to the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. Calculations suggest 46% of these “special settlers” died of disease, excluding those sent to the Siberian Gulag.

Between the late 1960’s and early ’80’s such draconian policies eased. In 1991 a Tartar parliament was formed to voice their people’s concerns. But by March 2014 relations between Russians and Tartars had deteriorated over Moscow’s control of Tartar affairs. Today, then, their position looks bleak, as they have no legal rights over their property or land. These rights were not restored to those returning from exile during the years of Perestroika, meaning legal domicile cannot be proved in a Russian court. The situation is analogous to the position of Jews returning from concentration camps after World War Two who could not obtain legal possession of their property in Poland or Germany. “Happy is the country without a history,” as someone once said.

The fact that the Tartars are just one ingredient in the melting pot of current events should, it is hoped, give an idea of how sensitive matters are.