Emile Zola versus the French Republic

Emile Zola (1840-1902) is a French writer who is now well known for his works of literature. Part of his quality comes from the passion he had for addressing issues on the inequality and injustice he saw around him in the French society of his time, which created one of his most famous (non-fictional) pieces of writing, J’Aaccuse – and which forced him out of his own country into a miserable exile in England…

Zola was a middle aged man in 1858, a year of great political turmoil in his native France. The turmoil had a name: the Dreyfus Affair; or more specifically Alfred Dreyfus, a French Army Officer, who was accused of passing military intelligence to the Germans. Found guilty on the contents of false papers, he was sentenced to life imprisonment on the infamous tropical hell of Devil’s Island. However, the truth was that the culprit was another officer, Major Ferdinand Esterhazy, who was the traitor. The army hierarchy simply could not allow “one of their own” – a catholic monarchist from an ancient French family – to have any blame anywhere near him. Instead they were resolved to avoid what would be a great national scandal, at any cost.

Dreyfus himself came from a wealthy Jewish family, who had their business in the province of Alsace Lorraine – also claimed by the Germans and where a number of the population were German speakers. A convenient combination of geography and antisemitism were hereby enough to find Dreyfus guilty (He was to be part of an “international Jewish syndicate” plotting to overthrow the Republic).

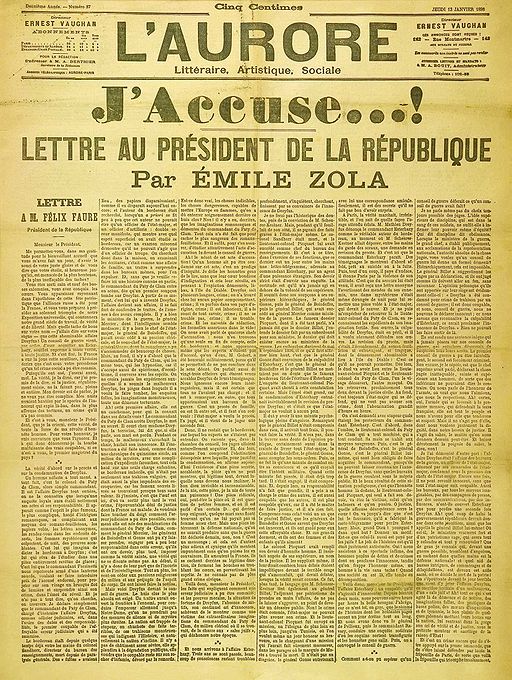

Zola, as a liberal, together with an increasingly like-minded press, denounced the elite’s verdict in a front page open letter article in “L’Aurore”, entitled J’Accuse. It was directed to the French President, Felix Faure, and in it Zola made sure he named Esterhazy as the true culprit. This deliberately courted prosecution for libel, but forced the French General staff to prove their case in a civil court rather than a closed court martial.

In the event, Zola was given a one year custodial sentence and a fine. Before he could be taken to prison, though, Zola fled the country and crossed the channel to England, taking with him hardly more than the clothes he was wearing. He was helped there by his translator and friend Edward Viztelly and was thus able to find residence in various hotels in and around London. As a writer and as a man cut off from home, in a city and country he fast grew to hate (the people, the food…), he was to suffer great loneliness there, and two nervous breakdowns. However, eventually he was to be allowed home, in June the following year, with his sentence commuted to a pardon. He accepted this and was able to go free, though it meant he had to admit guilt. Full exoneration would only be granted posthumously, but there was some justice, as he was to have the pleasure of witnessing the regime’s fall before he died.

Despite the fact Zola’s personal life story ended without full absolution, his legacy was one of greatness. Whilst the French Right wing establishment failed, and Esterhazy would die in obscurity, Zola received two Nobel prize nominations, in 1901 and 1902, the year of his death. His literary works have stood the test of time, and so it can be said that ultimately his was the last word.