Is Anybody Out There?

Astronomers have long since given up on the possibility of intelligent life elsewhere in our own solar system. But they are increasingly excited about the possibility of finding it on planets orbiting other stars. Such planets are called exoplanets.

Over 3000 exoplanets have now been discovered and the number increases every year. But for an exoplanet to support intelligent life, it has to satisfy three non-negotiable criteria. These are:

1. the correct chemical composition

2. the right temperature

3. extreme longevity.

First, life on Earth is based on the element carbon, and this is for a very good reason. Carbon is the only element which forms enough different compounds (proteins, nucleic acids and so on) to produce something as complicated as a biological organism. So an exoplanet which is a realistic candidate for supporting life must be rich in carbon.

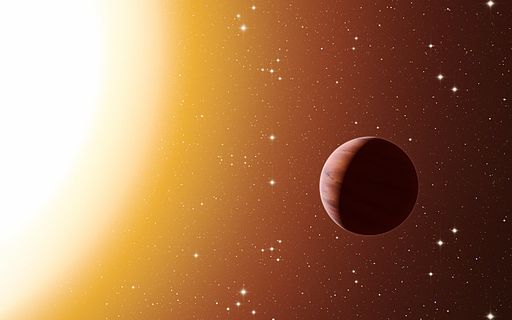

Second, the planet must have liquid on its surface, ideally water. Life depends on chemical reactions which take place in solution, and these simply cannot happen in a gas or a solid. The ideal liquid for this job is water, because water dissolves so many other materials. So our life-bearing planet needs a good supply of water, and also surface temperatures between 00 and 1000 C. This means a near-circular orbit, the right distance away from its star: not too close (or it would be too hot – all the water boiled away) or too distant (or it would be too cold – all the water frozen as ice).

These two criteria already rule out the vast majority of the exoplanets discovered so far. But it is the third one which is perhaps the most intriguing. It has taken about 3500 million years for intelligent life to evolve on Earth, and this length of time is not so very different from the lifetime of a star. So we need our planets to be orbiting a star with a relatively long lifespan.

Strangely enough, there is an inverse (upside down) relationship between the lifetime of a star and its brightness and size. Contrary to what you might expect, big stars are short-lived. They burn more brightly and so use up their fuel faster. The longest-lived stars are small, dim and inconspicuous. So, the brightest star in our sky, Sirius, at twice the mass of our Sun, will only last about 1700 million years; while the really cool dim ones can be expected to last thousands of times longer.

Thus it is that exoplanet searchers are paying special attention to small, dim stars rather than spectacular bright ones. And just recently they may have hit the jackpot. Three Earth-sized planets have been found orbiting the unassuming star 2MASS J23062928-0502285 (now nicknamed TRAPPIST-1) in the constellation Aquarius. This is an ultra-cool red dwarf star, not much bigger than our own planet Jupiter, and one of our stellar nearest neighbours. Astronomers think that these planets may be our best hope yet of finding life outside the solar system.

You can find out more about these newly-discovered planets at http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/three-potentially-habitable-worlds-found-around-nearby-ultracool-dwarf-star?utm_medium=email&utm_source=alumnewsletter , and use a calculator for finding the life-expectancy of stars at http://mrphome.net/starlifecalculator.htm