The Origins of Democracy

At the present time the concept of democracy and how parliament is run, particularly in the UK, is under the microscope. But where did the idea of democracy and parliament come from?

As with so much of our modern culture, we need to look to the ancient Greeks to find the earliest foundations of the democratic system. Even the word ‘democracy’ comes from the Greek language. The word ‘demokratia,’ when translated literally, means ‘people power,’ and referred to the ‘masses’ having a say in the running of their region. In the fourth century BC, Greece was made up of 1500 separate areas or ‘poleis.’ Most had their own democracy, although a few remained under the control of the rich elite. They were known as ‘oligarchies.’

The oldest democracy belongs to the Greek capital of Athens. Its earliest beginnings as a future democratic city can be attributed to the statesman and poet Solon. Although not a democratic, in approx 600 BC, he set down a framework of political reforms which, while largely ignored at the time, were later adopted by an aristocrat called Cleisthenes.

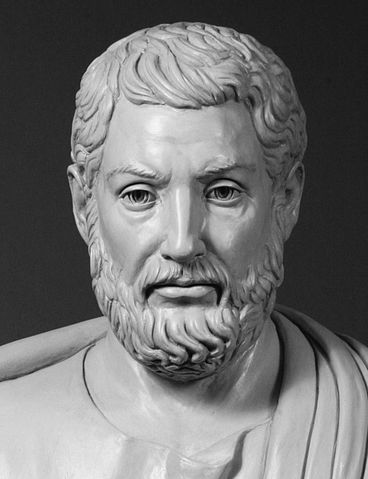

Cleisthenes

The grandson of a tyrant, Cleisthenes (pictured) seems an unlikely pursuer of democracy. However, after witnessing the actions of his former brother-in-law, Peisistratus, who seized power in Athens three times before establishing a dictatorship and passing control of Athens over to his ruthless son, Cleisthenes became increasingly sickened by the violent manner with which the region was ruled. In 508 AD, he began to push for radical political reform. Cleisthenes’s stand against elite rule was to mark the dawn of an Athenian democratic constitution, and pave the way for a political model that was, eventually, to be copied all over the world.

Athenian Democracy

Athenian Democracy – and the Greek democratic system that slowly followed it – was not like the system we recognise in the modern world. When democracy was first adopted in the USA, Abraham Lincoln did famously claim to be following the Greek ideal, and that there would be a ‘government of the people by the people for the people’, but this was never likely to become a reality. It always had been before, and likely always will be.

Modern democracy chooses its representatives by taking cast votes from everyone over the age of 18, with only a few exceptions, in elections. In the Ancient Greek system, 500 officials and jurors were selected by ‘the drawing’, a system of drawing lots for power. This method ensured that everyone eligible to vote had an equal chance of representing the people, not just the rich and powerful.

These 500 new politicians served for a twelve month period, and were awarded with a small payment to compensate them for their loss of earnings while they were working for the region. They were responsible for making new laws and updating old ones. However, their suggestions could not become law unless the citizens of Athens voted them in. To vote, citizens had to attend the assembly (an early version of Parliament) on the day the vote was to be taken, and make their opinion known.

As with modern democracies, in their early stages these small parliaments did not permit women a voice. In addition, you were not entitled to have your say if you were foreign or a slave. Another thing that certainly does not happen in today’s parliaments is the practise of ostracism. This worked in the opposite way to an election, when the voting public could decide which of their politicians should be exiled, or ‘ostracised’, from the region. Voters would write the name of the politician they wanted removed from power on a piece of broken pottery and, if over 6000 people had written down the same name, that person would lose their position – and be excluded from the region.

This Athenian system of direct democracy, where the region was truly run by the local people, lasted for almost 100 years. It came to an end when Athens lost the Peloponnesian War against Sparta. After that it was replaced by a court system, in which jurors randomly selected from the population, would administer the area, taking the world one step closer to the democracy we recognise today.